If you’ve ever been to a Passover Seder you may have discovered a few things:

- Manischewitz stains.

- Matzah always seems more cardboardy than it actually is.

- A horseradish-eating contest always seems more fun than it actually is.

- On Passover, the Jewish people are bound by tradition to drink multiple glasses of wine on an empty stomach. It’s in the book, people!

- Parsley was not meant to be eaten straight.

And you’ve probably also heard of the Four Questions. [If you haven’t, I’ll wait while you Google.]

As a dealer-certified Nice Jewish Boy and the youngest in my family, I grew up singing the Four Questions at Passover. As a dad, I taught my daughter to sing them this year. (Cue “Sunrise, Sunset.”)

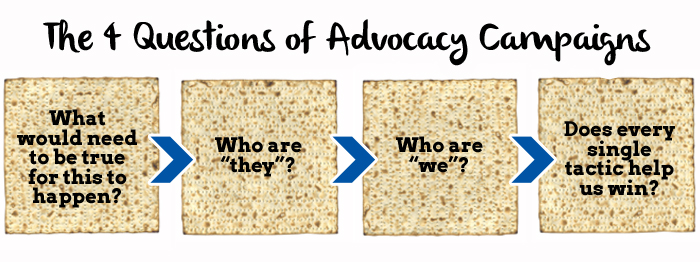

And as a campaigner, I’ve learned that anyone who works in advocacy would do well to take a page from the Passover Seder. (Not literally! We have to use those haggadahs next year! Oy, but I kid.) People say Passover can be boiled down to four essential questions. Turns out the same is true of planning an advocacy campaign.

Just like the Four Questions at a Seder, the Four Questions of advocacy are distilled from decades of experience by people who really, truly know their sh*t or stuff. M+R has used this model (and its blond, crunchy cousin from Montana) to plan lots of campaigns that have boldly stuck it to the Pharaohs of our time.

These questions are designed to spare you from wasting your time doing stuff that won’t accomplish your goals. And they work like…well, a miracle.

Question א: What would need to be true for this to happen?

This question cuts to the heart of your ultimate goal. What would the world need to look like for us to win this campaign? What would the political reality need to be? What would the media need to be saying? (In a sense, it’s the ultimate “How might we…” question for advocacy.)

Sometimes, the answers will be things you don’t think you could possibly accomplish. Things like, “We’d need three unmoveable Republican senators to switch their positions publicly.” Or, “CarMax would have to be getting so much bad publicity that it’s willing to take a hit in profits to make it go away.”

That tightening you’re feeling in your chest? That impossibility? That’s good. It’s what gets you to think big and figure out what smaller goals you’ll need to accomplish along the way. It’s what gets you to do things like make weird alliances or change your messaging entirely. It’s what helps you find the critical missing piece you’d need to have in place to really finish the Seder.

For an example, take this question we were batting about with our friends from the Wildlife Conservation Society last year: “What would need to be true in order for us to stop the poaching of 96 elephants per day in Africa?”

The big answer went something like: “We’d need to cut off the international market for poached ivory tusks.” Then we kept going… To stop the market, we’d need to get President Obama to sign a nationwide ban on ivory sales. And for that to happen, he needs political cover. What does that look like? Probably both a massive grassroots movement with some political teeth and a few state bans already on the books.

Boom. There’s your campaign. All from a single, magical question.

Question ב. Who are “they”?

You’ve got your overall goal. Now you need your target (or a progressive series of targets). Who ultimately has the power to say “Yes?” Whom do you need to pressure or persuade?

Sometimes the answer is obvious, sometimes it’s deceiving. When we were helping get Save Darfur up and running in the early days, you’d think the campaign’s obvious decision-maker target would be the UN or the US Secretary of State right? Nope. The first target that could get us the things we needed was Warren Buffett. That’s a story for another day. But believe me when I tell you — your target may be deceiving.

Answering whom isn’t enough. You also need to figure out who they are. What makes them tick? What do they care about? How have they responded to pressure in the past? What worked, and what was the threshold it had to reach?

There’s another “they” you need to figure out at this step: all the sub-targets who might influence your main target’s decision. These influencers could be community pillars, trade groups, faith leaders, select journalists, the target’s political “family,” etc. Even the target’s actual family (e.g. the classic “I was a bigot but my LGBT son/niece/sister changed my mind” narrative).

Once you know that, you have a bare-bones version of a “power map” — a constellation made up of both your target(s) and their influencers. Then you’ll want to dig deep and figure out if your organization’s board members, staff, or donors (or those of your coalition partners) have connections to that map. Only at this point can you decide on how to balance inside pressure vs. outside pressure in your campaign.

(Someday I’ll write another blog post on this. Working title: Power Maps, Persuasion, and Purim. For now, here’s a great resource on how this works.)

Onward!

Question ג. Who are “we”?

Who are the messengers, audiences, or partners who can move the needle here?

This question helps you think creatively about who’s going to be with us, how we’re going to leverage them to reach that constellation of targets and their influencers. Think about how “we” can be broken down into interest groups or constituencies. Would your issue benefit from a bunch of doctors coming together? A bunch of state reps? A bunch of indie bands?

This step isn’t just about who you HAVE speaking out, it’s about who you NEED speaking out. (To get back to “How might we” for a second, this is a good time to think through your specific influencers, one by one, and ask “How might we get them to become evangelists? Who would they need to hear from on this issue, and what would they need to hear?”)

Quite often, the answer involves finding the messengers — usually individuals — who are going to be able to tell your story best in the media. Who should be the face of the campaign? An Eagle Scout with two moms? A whistleblower scientist? A young girl who was almost killed by bacteria in bagged spinach? A young slave boy found in the rushes by the river, bearing a striking resemblance to Charlton Heston? This is where having a great story bank comes in handy. Again, a good topic for another blog post. (Working title: Story banks, Purim, and you.)

And this is also the step where you think through which audiences you’re trying to move to action. Before you write a single word, before you come up with a campaign name, before you sketch out a logo, you need to consider — deeply and honestly — who you’re speaking to. If your core activist is likely to be a woman between the ages of 45 and 64 (and aren’t they all?), don’t talk to her like she’s a 22-year-old hipster from Silver Lake.

And once you know who “we” are, you can figure out what “we” need to do.

Question ד. Does every single tactic help us win?

Just like a hangry pre-teen at a Passover Seder, you gotta be patient. Not until you’ve observed the rituals in full can you dig into the tasty stuff!

And as we all know, the tasty stuff is tactics. Sweet, shiny, attention-getting, brilliant (and occasionally misguided) tactics. You know, the fun part we all like to think about before we have a real plan in place.

Let’s create a cool, interactive online map!

Sorry, I knew that one would hit close to home.

Every tactic you come up with needs — nay, deserves — a gut-check. Does this point us toward changing the balance of power? Will it help influence our target? Will it make them feel some sort of consequences (positive or negative) if they do or don’t say yes? Is there something else more powerful we should be doing instead?

And, as always, you damn well better know whether it’s pressure or persuasion.

This is the step where your theory of change really falls into place. As you’re no doubt aware, your theory of change directly and plausibly connects your supporters’ actions to the outcome. It says, “If enough of us do X, we can accomplish Y — and here’s the proof that it can work.” But some of us forget that this theory isn’t just a handy device for writing compelling emails — it defines your campaign. If you can’t articulate it, you’re sunk. You won’t win, but more importantly, you’ll lose your activists.

Coda: Next year may all be free

Without thinking about it, a lot of us look at campaigns through the “goggles” of whatever we’re best at. Field goggles, media goggles, grasstops goggles, etc. (For me, it’s online scuba gear. You can take the campaigner out of the channel, but you can’t take the channel out of the campaigner.) The Four Questions FORCE you to take those goggles off and see more clearly. They force you to be channel-agnostic, because power structures are channel-agnostic.

So, now that we’ve parted the Red Sea for you, get going! Use the Four Questions to structure your next brainstorm! Use them as chapter headings for your next campaign plan! Use them to gut-check your board member’s terrible idea! Or your brilliant idea!

I guarantee, when you win, the victory will be sweeter than Manischewitz.